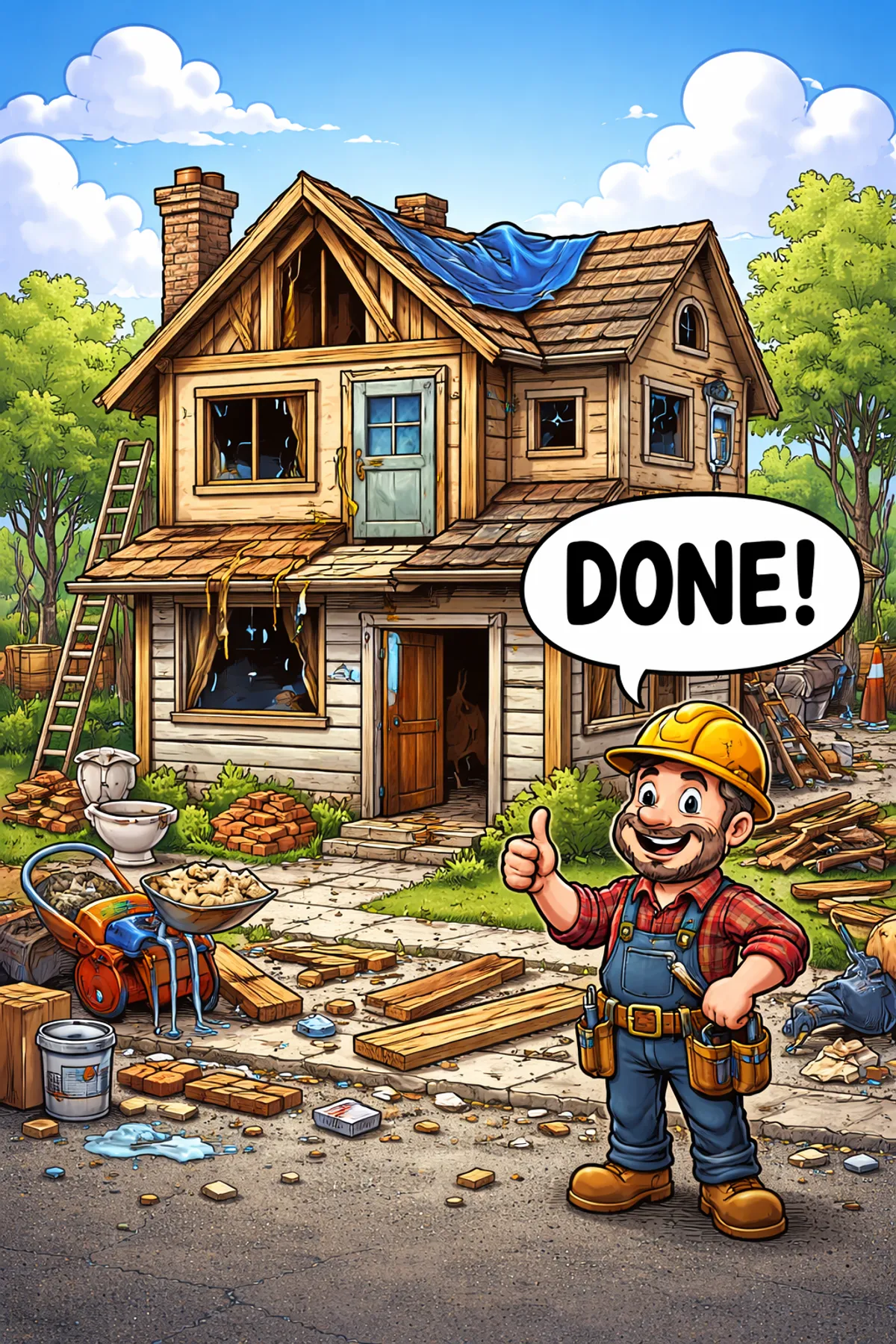

'Finished' Means Something Different Here

expats 24-12-2025

Introduction

When I first started writing this post, I wasn’t entirely sure where I was going with it. Is this post about what ‘finished’ means to the Filipinos? Or, is it a rant about the things that just weren’t present in the house when the foreman told me they were done? At this point, I can admit that the second one was the result of assumptions that I made that just weren’t based in reality of how things work here in the rural Philippines. So, this post is about what “finished” means for house construction in the rural provinces?

There are generally building codes, but these are not necessarily that detailed or enforced.

If you build or renovate a house in the rural Philippines, you may eventually hear the words:

- “Sir, finished na.”

- (“Sir, it’s finished.”)

You walk through the house—and immediately notice what’s missing:

- No smoke detectors

- No fire extinguishers

- No window screens

- No carbon monoxide

- The concrete isn’t smooth

- No downspouts were added (even though they some how managed to get all the drainage holes from the roof made)

- The rendered concrete walls are already cracking

- The paints cracking already (or my personal favorite, a year later, it starts falling off the ceiling).

- Not a single electrical socket has a ground (third pong).

Now, in all honesty, even in the US, every apartment I ever rented (or house I bought), there were not usually fire extinguishers included. I had to buy those myself. So, the fire extinguishers don’t necessarily belong in the list with the rest of these, but my girlfriend’s family were essentially making fun of me for spending money on fire extinguishers.

When you ask about these items, you’re met with blank stares, polite nods, or a confused silence that suggests you just asked for a unicorn enclosure. I installed the unicorn enclosure six months later…joke…or is it?

Their reactions aren’t incompetence. It isn’t dishonesty. And it usually isn’t refusal.

It’s a fundamental mismatch of assumptions.

In a previous life, I spent time in Panama. If you buy a condo or house in Panama, there are no light fixtures, no air conditioners, or anything else that most Americans or Europeans would consider “standard”. The exception would be a fully-furnished unit. The general rule in Panama would be that you are either spending 10% of the unit sale price on furnishings (including light fixtues, airconditioners, etc) or paying a premium to have that done for you by some third-party. I haven’t really encountered an equivalent of that in the Philippines so far. You generally won’t find that option in the rural provinces. The point is that the situation is not unique to the Philippines.

I still haven’t installed screens for the windows, but we do have screendoors now. The aluminum screendoors were made by a local gate shop. So far, I’m happy with the quality. The window screens are on the to-do list.

Most of these points are valid throughout the Southeast Asian tropics.

What “Finished” Actually Means in Rural Construction

In much of rural Philippines, a house is considered finished when:

- The structure stands

- The roof doesn’t leak (much)

- Electricity works

- Water flows

- Doors lock

- Windows close

That’s it.

Safety accessories, convenience items, and preventative features are not part of the mental checklist unless explicitly specified in writing—and often not even then.

To a local builder, electrician, or foreman:

- Smoke detectors are hotel equipment

- Fire extinguishers are factory equipment

- Window screens are optional luxury items

- Gas or carbon monoxide detectors are foreign paranoia

They are not considered standard residential components.

Why the Blank Stares Happen:

1. These Items Are Not Historically Used

Most rural Filipino homes:

- Are concrete or hollow block

- Have minimal enclosed spaces

- Traditionally cook with open flames

- Rely on natural airflow

For decades, families lived without:

- Smoke alarms

- Enclosed kitchens

- Gas detectors

- Centralized wiring standards

So when you ask why they aren’t installed, the unspoken answer is:

“Because no one has ever asked for this before.”

2. There Is No Enforcement Pressure

In many rural areas:

- Building inspections are minimal or symbolic

- Fire codes exist but are rarely enforced for single-family homes

- There is no expectation of liability after turnover (this may be the single greatest difference between the US and the Philippines)

If something isn’t required by the barangay or checked by the inspector, it’s not considered necessary.

From the builder’s perspective:

“If the government doesn’t require it, why would we add it?”

3. “Safety” Is Reactive, Not Preventative

Western construction culture is preventative:

- Assume things will go wrong

- Install systems before disaster

Rural Filipino culture is often reactive:

- Deal with problems when they happen

- Replace what breaks

- Repair after damage

This mindset isn’t reckless—it’s shaped by:

- Cost sensitivity

- Generational experience

- Limited access to insurance or emergency services

Installing something that might be needed later feels unnecessary when that money could be used today.

4. These Items Are Seen as the Owner’s Responsibility

Once the house is structurally complete, many builders believe:

“Everything else is furniture.”

And in their mental model:

- Smoke detectors = accessories

- Fire extinguishers = personal items

- Screens = decorative add-ons

So when you buy these yourself, the builder may genuinely assume:

“Ah, this is something the owner prefers. Not construction.”

- They Don’t Understand the Risk Model

Carbon monoxide detectors are a good example.

Many workers:

- Have never seen one

- Don’t know how it works

- Have never heard of CO poisoning as a household risk

Explaining it verbally often fails because:

- The danger is invisible

- The risk is statistical, not experiential

- “No one I know has died from this” feels like proof

So the response isn’t rejection—it’s incomprehension.

What This Means for Expats

If you are building or renovating in the rural Philippines:

- Assume nothing

- Specify everything

- Expect to self-install safety items

- Do not rely on “standard practice” — most of the time, it probably won’t meet your “western” expectations.

- Be on site at least part of each day the crew is working. If you don’t like the final result of some aspect of construction. Ask them to redo it, but remember, in most cases, you will be paying for whatever to be redone.

You are not arguing with resistance—you are colliding with a different definition of completeness.

To you, a house isn’t finished unless it’s:

- Safe

- Code-compliant

- Risk-mitigated

To them, a house is finished when:

- You can live in it today

- Both views make sense. They just don’t align.

The Practical Reality

Most expats eventually do this:

- Buy safety equipment themselves

- Install it personally or hire a specialist

- Accept that local builders will not prioritize unseen risks

- Stop expecting shared assumptions

It’s not personal. It’s not malicious. It’s cultural, economic, and experiential.

And once you understand that, the blank stares stop being frustrating—and start being predictable.

Thinking of Moving to the Philippines? Get Reliable Guidance

Online communities are helpful for general questions. For anything important, you still need accurate, professional, and updated information. E636 Expat Services helps foreigners with:

- Residency and long term visas

- Bank account opening

- Health insurance guidance

- Real estate assistance

- Business setup

- Retirement planning

- A smooth and secure transition into life in the Philippines

If you want to move with confidence instead of relying on random comments online, we can guide you every step of the way.

Book a consultation with E636 and start your journey the right way.